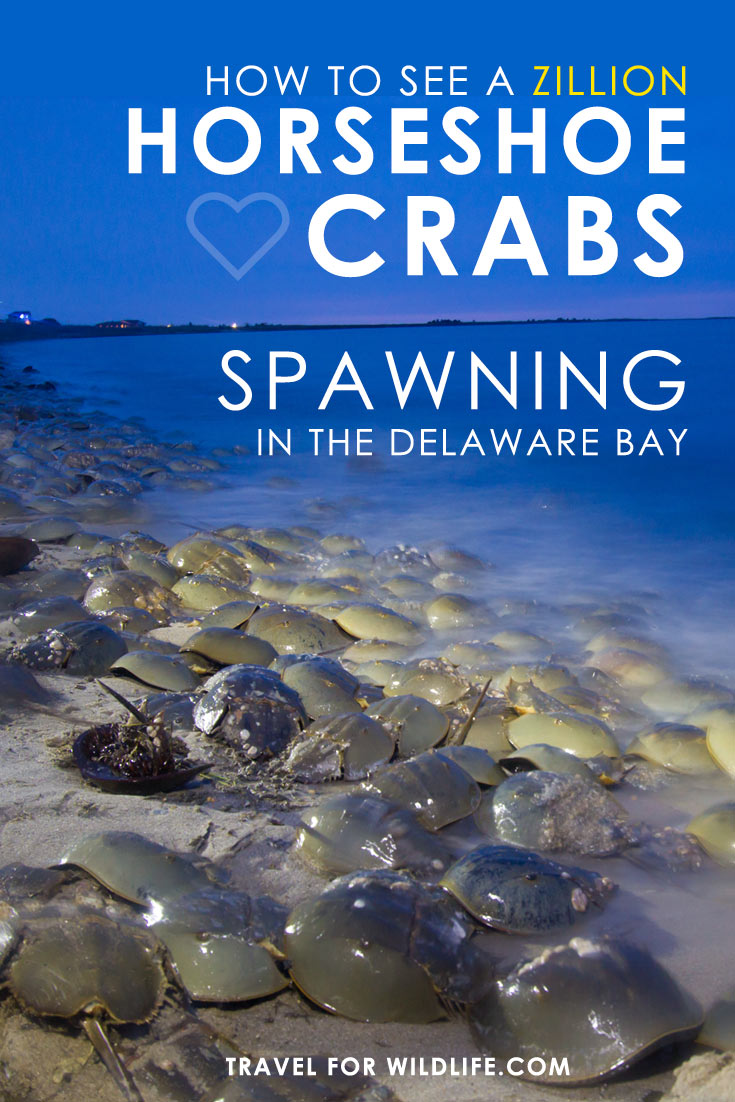

My friend Mike and I will be the only ones to witness the ancient gathering. Tonight, at high tide, thousands of bizarre-looking creatures will emerge from the ocean to perpetuate their species. I have come here to see the horseshoe crabs spawning in the Delaware Bay.

It seems impossible that one of the world’s great wildlife spectacles is going to happen right here on this quiet Delaware beach in an hour. There are no signs of the impending phenomenon. Just small waves lapping quietly at the empty sand. Even though fifty million people live within a three-hour drive of this spot, there’s not a single human to be seen in either direction.

(If you want to skip the tale, you can jump straight to the end where I tell you how and where to see horseshoe crabs spawning.) Keep on reading to learn about the amazing horseshoe crab blood (the horseshoe crab is one of the few blue blood animals!).

*This article may contain affiliate links. We receive a small commission at no extra cost to you.*

Mike and I look dejectedly down the beach in the gathering gloom. I’m trying to hype up the event since I’ve dragged him all the way out here but he doesn’t quite seem convinced. And I have to admit, I’m a little worried myself. High tide is an hour away and there is not a single horseshoe crab visible for miles.

How is it possible that tens of thousands of them will line these shores tonight? Has my research failed me? Was it all a big practical joke? Then I spot a large dark shape in front of us. It is a shiny brown dome, like a plastic construction helmet lying upside down in the sand, and it has a foot-long spike protruding out of one side. It’s the empty molted shell of an enormous horseshoe crab. Mike has no idea what a horseshoe crab looks like so when I hold the beast’s shell up to him his eyes widen. “Wow. That’s a lot bigger than I thought they would be. That looks like something out of Alien. I’m actually getting a little excited about this.”

Now the pressure is on and I don’t want to disappoint my friend. We trudge across the sand back to the car and drive into the nearby town of Milford to look for dinner and a drink. We sit by the window of the Park Place Restaurant (yes, there’s a Monopoly man on the sign) and drink a Mispillion River IPA without any clue that we are looking out over the very river for which it was named. Mike is the slowest eater in the world and I am getting antsy to get back out to the beach. When we finally emerge there is a dark blanket of clouds and a cold sheet of drizzle begins to fall on our heads. I’m not feeling hopeful but I have to try.

As night approaches, we drive the ten minutes of pastoral country roads back to Slaughter Beach in search of prehistoric creatures. It feels like the beginning of an 80’s horror film.

The sleepy little town is just a two-mile stretch of road that hugs the bay and is lined on one side with a row of modest summer cottages facing the gray sea. There is nothing but farm fields and salt marsh for many miles in every direction. There are no cars on the road, no residents to be seen. We park in one of the public beach access roads, which I select for its prophetic name: Marvel Drive. The small sandy lot, which was empty an hour earlier, now has two parked cars and I consider it a hopeful sign.

I pull on my sandals, grab my umbrella and camera gear, and two headlamps. 7:54 PM. Exactly high tide according to the tide charts. If there were any sun to set, it would be doing so in twenty minutes. But the solid clouds have robbed us of any possible golden sunset light. We step out of the low dune trail into the blustering wind to see an empty beach. A group of three people dressed in rain-proof jackets approaches us from the north carrying a large white square made of plastic plumbing pipe, one meter to a side. I recognize immediately what they’re up to from my previous online research. “Are you doing horseshoe crab surveys?” I call out across the wind.

“Yep!” replies an amiable, bearded young man as they huddle around us. I learn later, from the business card he leaves on my windshield, that his name is Matt Babbitt and he’s the manager of the nearby Abbott’s Mill Nature Center.

“Pretty slow tonight, huh?”

Matt smiles sympathetically, “Oh they’re coming out, head up that way a while. Seems like they’re all blowing up into the bend.” He waves to a dark area of the beach half a mile away. I thank him for the tip and peer into the distance. They must be the owners of the two cars because again we are the only people on the entire beach. With a bit more determination now, we stumble across the seaweed-strewn sand. I can’t believe the moment has finally arrived, the moment I’ve been imagining since first reading about the phenomenon in Wildlife Spectacles three years earlier. And then I see it.

It looks like a big brown salad bowl with eyes, embedded in the sand. There’s another on top of it off to one side. The waves wash over but they hold fast. It is a pair of mating horseshoe crabs. Our first of the night. Technically they’re not mating because there is no intercourse involved. They are actually “spawning”. The larger female digs a hole in the sand and deposits hundreds of tiny eggs.

Meanwhile, the smaller male latches on top of her back end (a posture known as amplexus) and fertilizes the eggs as she lays them. Somehow she knows when the highest tides are occurring in the few days surrounding new and full moon in late May and early June.

This zone, just below the highest water line, has the right combination of moisture, oxygen, and temperature for proper embryo development. Within a few weeks the tiny larvae will emerge into the waves looking like perfect micro replicas of their mother, but with a shorter tail.

For more than 400 million years horseshoe crabs have been performing this primordial ritual. It’s an unimaginable span of time, as if the creatures at my feet belong to an immortal lineage, one that had always been on planet Earth and always would be. Then, in the geological blink of an eye, humans appeared and decimated their numbers.

Blue Gold: The Story of Horseshoe Crab’s Blood

The unique, blue, copper-based horseshoe crab blood contains a special clotting agent that we use to detect bacterial contamination in our pharmaceuticals and medical implants. As detailed in this somewhat disturbing clip from the PBS documentary: Crash: A Tale of Two Species, half a million horseshoe crabs are captured each year, bled of nearly a third of their blood in a laboratory, and then returned to the sea “unharmed” in a different location.

However, the ERDG Horseshoe Crab Conservation Network states that as of 2016 roughly 70,600 animals die per year in the process. Worse still, more than ten times that number (750,000) are killed each year to use as bait in the commercial conch and eel fisheries. And that’s a substantial improvement compared to harvest levels 20 years ago. In 1999 about 3 million horseshoe crabs were harvested annually as bait for commercial fisheries. And before that millions more were being killed and ground up to support a thriving fertilizer industry around the Delaware Bay. Add to all this the steady loss of suitable spawning beaches due to human coastal development, it’s no wonder this immortal species is suddenly in danger of disappearing.

Update May 2017: A major pharmaceutical company, Eli Lilly, has announced that they are committing to the use of a synthetic substitute for horseshoe crab blood! This is a huge step toward ending the blood harvest of horseshoe crabs. Learn more about the “factor C test kit” in this article in the Atlantic.

How to Flip a Horseshoe Crab

We walk on and the shiny brown domes become more frequent. Some are tumbling sideways in the gentle waves, others cling to each other in small groups of twos and threes as the water washes over them. These crabs aren’t actually crabs at all. They’re more closely related to spiders and scorpions. They belong to an ancient lineage from the time of the trilobites. The American Horseshoe Crab (Limulus polyphemus) is one of only four remaining species of horseshoe crabs left worldwide. The other three are found only in Southeast Asia.

“Want to see what they look like underneath? This one’s been flipped upside down by a wave.”

Mike comes closer and peers down at the bizarre extraterrestrial anatomy to see ten spidery legs waving slowly in the air brandishing small pincers. “Woah. That’s crazy.” Her long spike of a tail points straight up at him.

“These guys have a really hard time flipping themselves back over again, so when you find one like this you should help’em out. Don’t worry, they’re not dangerous.” Just a little bit creepy. I reach down and grab her carefully by the side (I can tell she’s a female by her huge size) and roll her over gently. Her long spiky tail is still jack-knifed under her and hits the sand first, but she relaxes into a flattened position as soon her flailing feet touch ground. Immediately she begins to scuttle back toward the water. I wonder how her unblinking eyes see me, glued to the top of her carapace like dragonfly kaleidoscopes pointing left and right. It’s best not to pick them up by the tail because you might damage it. It’s the only tool they have for turning themselves back over.

Clearly it doesn’t work very well. I see many more flipped over ahead of us, trying to right themselves. It seems like a pretty bad design to me. I don’t know how they’ve survived this long.

Now the small groups are widening into congregations. They emerge from the waves by the dozen, males crowding around the laying females, attempting to add their genetic code to the mix.

Darkness descends quickly and we need our headlamps to dodge the bodies and flip the stranded. By the end of the evening we will have flipped well over a hundred.

The sand at the water line is quickly being replaced by shiny mounds, like goosebumps across the ocean’s skin.

Huh. This actually is pretty impressive. Though it’s hard to get a real sense of the scope of this phenomenon as we can’t see past the headlamp’s beam. It’s not until I set up my tripod and shoot some long exposures that I can see on my little screen that the amazing creatures go on and on far into the distance.

And this is just one of many spawning beaches around the Delaware Bay and the east coast of the United States. Once upon a time this spectacle must have been truly awe-inspiring. But there is still hope.

In 2004, this tiny town voted to declare Slaughter Beach a horseshoe crab sanctuary and to ban the harvest of horseshoe crabs from their beaches. Perhaps as more bay-front communities follow suit, numbers will rise again. If you want to help this immortal species march on into the future, share this post, help raise awareness, join a volunteer walk to flip crabs, support the creation of a synthetic substitute to the LAL found in horseshoe crab blood, reduce consumption of conch and eel whose fisheries rely on horseshoe crabs as bait, and support the ERDG for all the great conservation work they’re doing.

How to See Horseshoe Crabs Spawning in the Delaware Bay

If you learn the trick, you too can witness this amazing wildlife spectacle. Here’s how I managed to see the horseshoe crabs spawning in the Delaware Bay.

- Choose the right dates

- Choose a good beach

- Arrive at evening high tide

1) Choose the Right Dates (When to See Horseshoe Crabs Spawning)

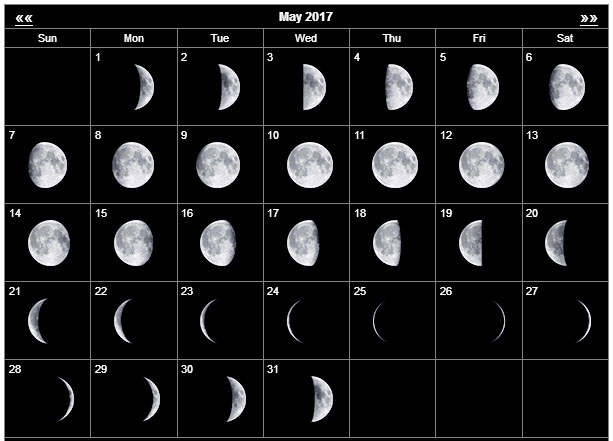

Horseshoe crabs spawn in May and June at the highest tides. These occur during the three days before and after full moon and new moon. So you have to check out a moon phase calendar to see which dates meet these two criteria. For example, I looked at a moon phase calendar for May 2017:

and saw that the new moon (May 25th) fell right in the center of my required time of year (May to June). So my optimal viewing window (from three days before to three days after new moon) was May 22 through May 28. Alternately I could have chosen the next full moon which is June 9, giving me another optimal viewing window of June 6 through June 12. I chose the beginning of my window because the timing of evening high tide was before sunset and because many of the public beaches close at dark, or in the case of Slaughter Beach, at 9 PM.

It’s possible to catch horseshoe crabs spawning anytime during May and June, so you have four peaks to choose from (full or new moon in May, and full or new moon in June.) If you don’t feel like figuring all this out for yourself, here are the best dates to see horseshoe crabs spawning in the Delaware Bay over the next few years.

Best Dates to See Horseshoe Crabs Spawning in the Delaware Bay 2023 – 2030

2023

- May 19 (New Moon) Good Window: May 17 – May 21

- June 3 (Full Moon) Best Window: June 1 – June 5

- June 18 (New Moon) Good Window: June 16 – June 20

2024

- May 23 (Full Moon) Good Window: May 21 – May 25

- June 6 (New Moon) Best Window: June 4 – June 8

- June 21 (Full Moon) Good Window: June 19 – June 23

2025

- May 12 (Full Moon) Good Window: May 10 – May 14

- May 26 (New Moon) Best Window: May 24 – May 28

- June 11 (Full Moon) Good Window: June 9 – June 13

2026

- May 16 (New Moon) Good Window: May 14 – May 18

- May 31 (Full Moon) Best Window: May 29 – June 2

- June 14 (New Moon) Good Window: June 12 – June 16

2027

- May 20 (Full Moon) Good Window: May 18 – May 22

- June 4 (New Moon) Best Window: June 2 – June 6

- June 18 (Full Moon) Good Window: June 16 -June 20

2028

- May 24 New Moon) Good Window: May 22 – May 26

- June 7 (Full Moon) Best Window: June 5 – June 9

- June 22 New Moon) Good Window: June 20 – June 24

2029

- May 13 (New Moon) Good Window: May 11 – May 15

- May 27 (Full Moon) Best Window: May 25 – May 29

- June 11 (New Moon) Good Window: June 9 – June 13

2030

- May 17 (Full Moon) Good Window: May 15 – May 19

- June 1 (New Moon) Best Window: May 30 – June 3

- June 15 (Full Moon) Good Window: June 13 – June 17

2) Choose a Good Beach (Where to See Horseshoe Crabs Spawning)

Although Horseshoe crabs may spawn on protected beaches anywhere along the Atlantic Coast of the United States and even up into the Gulf of Mexico, (we’ve seen horseshoe crabs mating in Cedar Key on Florida’s west coast) the Delaware Bay is where the highest concentrations occur. Here is a map of some of the best beaches to watch horseshoe crabs mating.

According to the official horseshoe crab surveys, some of the highest numbers have been reported at Slaughter Beach and Pickering Beach on the Delaware side. Keep in mind that many of the best horseshoe crab spawning beaches on the New Jersey side are closed at this time of year. This is intended to protect the migrating shorebirds who depend on horseshoe crab eggs to store enough energy to complete their migration. This is especially true for the threatened Red Knot who migrates all the way from the southern tip of South America to breed in the Arctic each year and times their migration to coincide with horseshoe crab spawning in the Delaware Bay.

Check the list of New Jersey seasonal beach closures to see what kind of access is available. Most of these beaches have a narrow strip open to the public right at the access point, with closures to either side. This means you have to get lucky that the spawning concentration is occurring right at the open section. Another great option for visiting closed beaches on the New Jersey side is to join an organized volunteer walk to flip stranded horseshoes crabs with “reTURN the Favor” program.

To see a list of more good spawning beaches check out this nice map from Celebrate Delaware Bay.

3) Arrive at High Tide (How to Time it Right to See Horseshoe Crabs Spawning)

To see the horseshoe crabs, you have to arrive at high tide. Although I’ve seen photos of spawning crabs in daylight, I personally did not see any spawning crabs during the morning high tide, only at the evening high tides. Arriving at high tide is a simple matter of looking up tide charts for the location you intend to visit.

For example I decided to visit Slaughter Beach, DE so I searched tides4fishing.com for tide charts for Milford DE (Mispillion River Mouth). You can choose which month you want to see by adjusting the calendar controls at the top of the page. You have to scroll way down the page to see the tide charts. Here’s what I found:

The blue times are high tides and the red times are low tides. The number beneath each time shows exactly how high or how low the tides are. By studying this chart you can see that the evening high tides are higher than the morning high tides. (For example on Friday May 26 the morning high tide was at +5.1 feet and the evening high tide was at +6.6 feet.) which is perhaps why the crabs only chose the evening highs to spawn during my visit.

In order to maximize my chances of photographing the crabs in natural light, I looked up the sunset time by typing “sunset milford, DE May 23, 2017” into Google, which conveniently returned the answer at the top of the page as 8:15 PM. Therefore I knew that the only evening high tide that would occur before sunset during my optimal viewing days was on Tuesday May 23 at 7:54 PM. That was my magic date and time.

Why I Chose Slaughter Beach to watch Horseshoe Crabs

I chose Slaughter Beach for 6 reasons:

- Plenty of public beach access roads with free parking.

- Very high concentrations of horseshoe crabs reported in previous surveys.

- The beach is open to the public during spawning season.

- The beach is open til 9PM (unlike Pickering or Kitts Hummock which close earlier)

- Slaughter Beach is a horseshoe crab sanctuary that doesn’t allow harvesting.

- The sun sets over the water for the beaches on the Delaware side.

- Bonus: that awesome name.

I checked out some of the other beaches in the area and decided that Slaughter Beach was my favorite for watching horseshoe crabs mate. Both Pickering Beach and Kitts Hummock only had one public beach access with limited parking and I felt like I was invading someone’s neighborhood. Plus signs say that Kitts Hummock beach closes at dusk, while Pickering Beach closes at 6PM! Not good for evening viewing.

Slaughter Beach, on the other hand, is open until 9PM. And they have a public pavilion behind the fire station with plenty of parking, as well as a bunch of educational displays, a picnic shelter next to the beach, and public restrooms! And don’t forget that cool town sign with a horseshoe crab on it!

Remember to be a good visitor if you go to Slaughter Beach. Do not cross private property, obey the beach closing hours (9 PM), flip stranded horseshoe crabs when you see them, and do not disturb feeding shorebirds! Thousands of migrating shorebirds depend on the horseshoe crab eggs to complete their migration. Give them their space, keep quiet, and let them feed.

Photography Tips (How to Photograph Horseshoe Crabs Spawning)

Even though I had a horrible cloudy rainy night, I managed to get some pretty cool pictures of horseshoe crabs in Delaware Bay. Here’s how I did it.

The trick to shooting after sunset or on a dark cloudy evening is long exposures. In order to do this, you need a decent tripod. I use my traveling tripod Gitzo GK1545T because it is super solid for a compact, lightweight tripod. Then I use a digital SLR with a wide angle lens, I use the Canon 10-22mm Lens.

Long exposures accomplish a couple of neat tricks at the same time.

- You can expose the background properly (unlike standard flash photos) including dark clouds or stars

- You get cool ghostly effects with the waves

- It gives you a chance to do some “light painting” on the horseshoe crabs.

Normally, long exposures don’t make a lot of sense in wildlife photography because your subject tends to move and create ghost images. Luckily, horseshoe crabs don’t move much when they’re spawning. If one does move, it will create a point of interest and a sense of motion. Since I didn’t have time to play around with a lot of manual settings, I simply set it to automatic exposure (the P for Program mode) kept the ISO low (100 or 200 to minimize noise) and then I let the camera decide what shutter speed it wanted to use. Shooting in dark conditions this way will generally cause the camera to choose the biggest aperture possible (in my case f3.5) and then leave the shutter open as long as necessary for proper exposure. With this technique I was getting 8 to 10 second exposures which worked out great for a bit of light painting with a headlamp.

Things to watch out for. Usually, shooting with a wide open aperture can give you depth of field problems (like your background isn’t sharp) but with a super wide angle it’s not as much of an issue. I manually set my focus using a headlamp on a crab about 6 feet away and left it there so I wouldn’t be waiting for my camera to find a focus point in the dark. This provided a workable depth of field for me. If you find automatic exposures are making the scene a little brighter than you want, you can dial down the exposure adjustment a stop (which I did). Another challenge is keeping your tripod stable when waves are washing over the feet. For this one you just have to get lucky and hope the feet don’t sink as the wave pulls out. If it’s not working, you’ll have to pull back and shoot from just above the water line.

Light painting tips. Light painting is using a light source to expose parts of your image during a long exposure. Headlamps are my favorite tool. Lately I’ve been using a Petzl – ACTIK CORE Headlamp because they’re super bright for their small size, and rechargeable. I had my friend Mike stand farther down the beach outside of the frame with one headlamp and I stayed near the camera with another. When I shouted “GO” Mike and I would both slowly sweep the tops of the horseshoe crabs from a very low angle to create interesting shadows and highlights until the shutter closed 10 seconds later. You have to be careful not to over expose any single area with this technique and it will take a few experiments to see what method is working best for your shot. Plus it’s tons of fun!

Another great technique to make the beach look really crowded with horseshoe crabs is to shoot with a longer lens down the length of the beach. This will compress the crabs closer together visually. I used my Canon EF 100-400mm Lens set at around 130 mm. But by the time I tried it, it was so dark that it was a real challenge to keep my longer lens stable in the wind. If you get better luck than I did and have a bright sunset, this would be a great technique to try.

Where to Stay

If you’re looking for horseshoe crabs on the Delaware side beaches like I did, then you’ll find the most hotel lodging options in Dover. It’s about 30 minutes from Slaughter Beach and only 15 minutes from Pickering. However, I would personally rather stay in Milford which is only a 10 minute drive from Slaughter Beach (which has no hotels of its own) and it’s smaller and cuter. There are a few hotels in town to choose from including a Hampton Inn, a Days Inn and a cute B&B called Causey Mansion.

But my favorite option of all would be to rent a cottage right in Slaughter Beach and be able to watch horseshoe crabs right outside my front door. There are a bunch of cute rental cottages in Slaughter Beach on VRBO. Treat yourself to an oceanfront cottage rental for a few days and watch horseshoe crabs at night and shorebirds by day!

Further Reading about Wildlife Gatherings

Want to learn about more amazing wildlife spectacles in the United States and around the world? Check out the beautiful coffee table book Wildlife Spectacles: Mass Migrations, Mating Rituals, and Other Fascinating Animal Behaviors a newer version on a similar theme. A Year of Watching Wildlife is another one of my favorites for finding wildlife travel inspiration.

Want to check out another adorable little town where you can see horseshoe crabs mating and go kayaking with dolphins? Then read this article next: Why Cedar Key is Our Favorite Place to Kayak With Dolphins in Florida.

Did you enjoy this article? Pin it!

Hal Brindley

Brindley is an American conservation biologist, wildlife photographer, filmmaker, writer, and illustrator living in Asheville, NC. He studied black-footed cats in Namibia for his master’s research, has traveled to all seven continents, and loves native plant gardening. See more of his work at Travel for Wildlife, Truly Wild, Our Wild Yard, & Naturalist Studio.

Megan

Tuesday 1st of May 2018

Hal, stumbled upon this, and so excited to see you mention ReTURN the Favor NJ! Thanks for the shout-out! It is an awesome way to get to see this phenomenon!

Hal Brindley

Wednesday 2nd of May 2018

Hi Megan, my pleasure! It's a really great program you guys are doing and we're happy to promote it! Thanks for reading! -Hal

Ivan Vesely

Monday 23rd of April 2018

Great story Hal,

I am planning the trip with my family for this year. Based on your info, I determined that the evenings of May 16th and June 13th would be ideal - new moon, very high evening tides at Slaughter Beach. What is unclear though, is how many time they do this - just once, or do they do this a few times during this window? For example, both June 13th and 14th are good night according to the tide charts. Do they go up both nights? A quick email back would be greatly appreciated. Thank you!

Sunday 29th of April 2018

Hi Ivan, good question. I'll shoot you an email as well, but in case anyone else has the same question here's a quick answer. The horseshoe crab are generally highest on the night with the highest tide (full and new moon) but there are still significant numbers coming out to spawn for each of the two or three nights before and after. So for about five nights in a row you have a good chance of spotting a bunch. Best of luck! -Hal

Kathleen Nolan

Tuesday 27th of February 2018

Dear Hal, Very interesting article about horseshoe crabs. I am determined to see them this year! Would I have permission to use some or one of your spawning photos in a case study for teaching I am writing on horseshoe crabs? I hope to publish it in the National Center fir Case Studies in Teaching Science at University at Buffalo. I am a biology professor .