Frogs speak to me. I don’t mean literally (yes, Kermit did talk to me a lot as a kid), but they certainly stir a deep fascination. The big smile, the beautiful colors, the magical transformation from water-breather to air-breather; what’s not to love? Yet, sadly, these endearing creatures are also the most threatened vertebrate family on earth.

and is currently listed as Endangered by the IUCN. (Image © Alejandro Sanchez/IUCN)

A recent study found that about half of all 8,000 known frog species are threatened with extinction. While this shocking figure is primarily due to our relentless destruction of freshwater habitats, frogs now have another challenge to contend with: climate change. Thankfully, a dedicated group of researchers in Puerto Rico is trying to keep our amphibian friends from croaking with a sophisticated computer modeling approach.

It can be a little challenging to visualize how climate change affects the survival of a species so let’s put it in a human perspective. Say you live in Florida and your bedroom is upstairs, but you have a spare bedroom on the ground floor. If your AC stops working upstairs and it’s now a hundred and ten degrees up there, are you going to sleep there anyway and suffer a heat-stroke? Of course not. Now imagine your downstairs bedroom is already occupied by your significant other’s craft beer brewing equipment and smells like fermenting barley. You have suddenly become a species without a climate refuge.

Are Puerto Rico’s protected areas in the right place?

Puerto Rico faces a similar dilemma. As a fairly small “house” (smaller than the state of Connecticut) there are relatively few rooms that animals can move to if the one they live in gets too hot or too dry. A recent study, published in Biodiversity and Conservation, has concluded that we may need to rethink the current protected area network in Puerto Rico to provide suitable refuges for endemic frog and bird species as climate conditions shift.

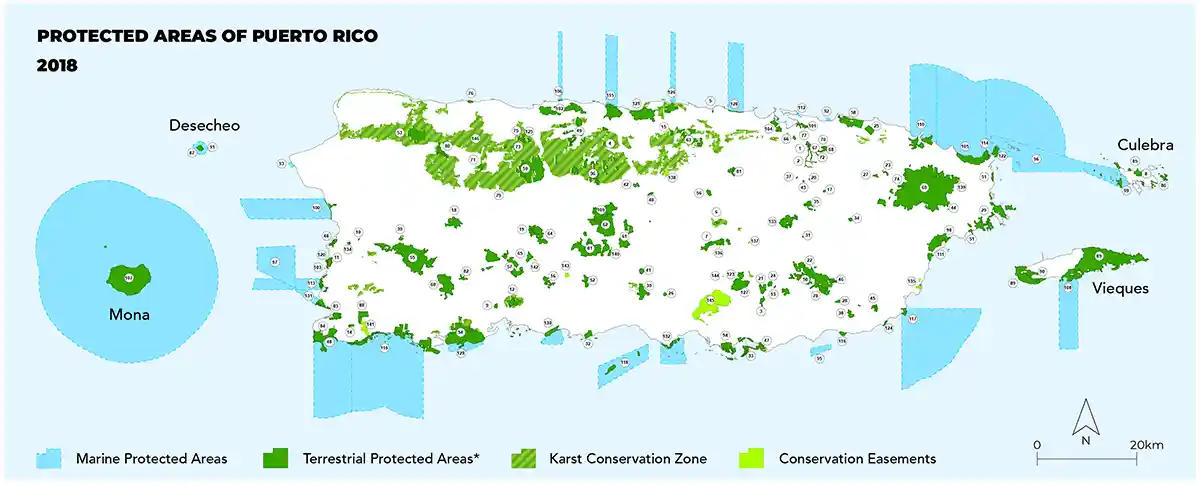

Puerto Rico is a Caribbean island (and an unincorporated territory of the United States) with 16% of its land area currently protected. This is pretty good considering that the U.S. as a whole has only 12% under some form of protection. El Yunque, in the northeast corner of Puerto Rico, is the only tropical rainforest in the U.S. National Forest Service, and a beautiful wildlife watching destination. The problem is that this extensive network may not be in the right place 20 or 40 years from now. So how do scientists figure out where the right place will be? With a little help from models.

Don’t give up on that modeling career just yet.

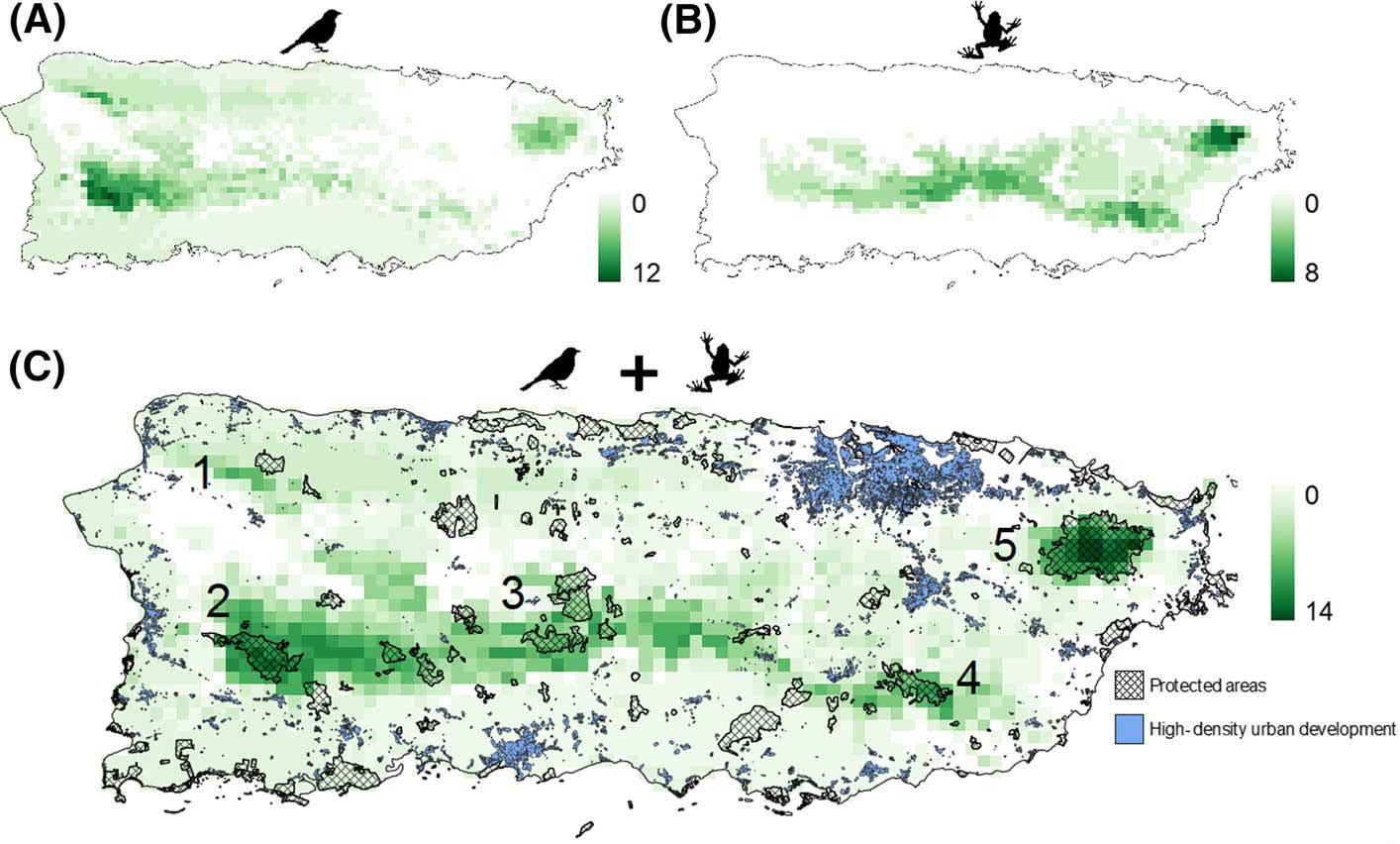

If your parents ever tried to convince you not to pursue a career in modeling, you can go tell them now just how wrong they were. While it’s true these models aren’t likely to make it to the cover of Vogue, they are rather beautiful in their own way. Species Distribution Models (known as SDM’s) use complex algorithms and fancy statistics to look at the climatic conditions where a species currently lives, and then project where those conditions are most likely to occur under various future scenarios.

While the concept seems simple, these computer models require a lot of accurate data to spit out useful answers. First you need to know exactly where a species lives, as well as where it doesn’t live. In a dense tropical rainforest, this is a lot harder than it sounds. But “sounds” are in fact the key to cracking the mystery.

A call for help? Recording frog and bird sounds with bio-acoustic monitoring.

Dr. Marconi Campos-Cerqueira works as a biodiversity scientist at Rainforest Connection in San Juan. He and his team used bio-acoustic monitoring to collect data on the presence of 21 species of frogs and birds by remotely recording their calls.

Listening to 9,000 one-minute recordings from 700 locations in Puerto Rico sounds like a job for an intern. But these days, computer programs can automatically identify animal calls by comparing them to a database of species identifiers. However, some calls are easier to identify than others. The Burrowing Coqui frog has a 94% chance of correct detection while the beautiful endemic Puerto Rican Oriole works only about 63% of the time. Arguably, these success rates are much better than your average college intern wearing a Wilco tee shirt.

A normal climate change impact study would then plug this range information into a Species Distribution Model, along with extensive climate data for the region, to find a new projected range under future climate scenarios. But Campos-Cerqueira’s team wanted to take it a step further. Their goal was to look not only at the present and the future, but the past as well, allowing them to find what they called Always-Suitable Areas.

Finding Refuge

These Always-Suitable Areas, or ASA, incorporate historical data to find the places that provide the greatest climate suitability across time, from 40 years ago, to today, to 40 years in the future. What they discovered was that these important climate “refugia” don’t always line up very well with Puerto Rico’s current network of protected areas.

In fact, only about 75% of the most climate-proof bird refugia are currently protected. The situation is far more dire for frogs, with a dismal 39% under protection. However, this disheartening news comes with a ray of hope. Most of these ASA have not yet been destroyed by development, and according to Campos-Cerqueira, “the establishment of larger protected areas, buffer zones, and connectivity between protected areas may allow species to find suitable niches to withstand environmental changes.”

Using models to forecast where species need to go can help us choose our protected areas today. And together we can help our froggy friends hop safely into the future. You can support conservation in Puerto Rico by visiting important protected areas like El Yunque National Forest and the Maricao State Forest, and by supporting organizations like Rainforest Connection who are conducting this vital research and working to expand protected areas.

Want to hear what a coqui frog sounds like? (The name should give you a hint!) Watch this video from Discover Puerto Rico to hear the night sounds of El Yunque and learn more about Puerto Rican culture and heritage.

Hal Brindley

Brindley is an American conservation biologist, wildlife photographer, filmmaker, writer, and illustrator living in Asheville, NC. He studied black-footed cats in Namibia for his master’s research, has traveled to all seven continents, and loves native plant gardening. See more of his work at Travel for Wildlife, Truly Wild, Our Wild Yard, & Naturalist Studio.

Lavinia

Sunday 29th of May 2022

Love your work! Thank you for what you do.