Russia.

It’s impossible for an American to even read that word without feeling at least a tiny twinge of emotional response.

Since I was a kid I’ve been subjected to anti-Russian propaganda. I can actually remember in the late 70’s when other eight-year-olds in my elementary school used the word “commies”. I had this vague notion that “the Russkies” were the bad guys. Then suddenly, names like the Ayatollah Khomeini began popping up on TV and us kids began to think that the bad guys now lived somewhere in the desert.

Once the cold war reached room temperature, I had little to go on in the way of real information about Russia. Sure, I saw the stereotypical portrayals of Russians on TV and movies. Cold-hearted spies. Sexy mail-order brides. Tough-guy mobsters. And, of course, old men wearing big fur hats standing in the snow drinking vodka.

I don’t read newspapers or watch the news. I don’t follow politics. The only information I had about Vladimir Putin came from watching a fictional caricature of him named Viktor Petrov on “House of Cards.” So when it came to Russia, I was the typical ignorant American.

But fifteen years ago, when I began traveling the world in search of wildlife and wild places, I started to gaze at that vast space on the world map. The biggest country in the world. Nearly twice the size of the next biggest. (Canada = 3.8 million square miles. Russia = 6.6 million square miles)

I began to fantasize about what wonders must lie in that vast wilderness. But I never really believed that I would ever set foot there. Kind of like the moon. Until the email came.

It was an invitation from a small Russian non-profit (the Dersu Uzala Ecotourism Fund) to visit one of several new ecotourism projects being developed in Russia. They could afford to pay for one of us to visit so Cristina told me to go for it. I accepted without hesitation.

My excitement multiplied when I was given a list of six regions in Russia to choose from, each with its own pilot ecotourism project that I could test drive. Belugas here, bears there. How could I possibly choose? But I also noticed that my anxiety was mounting in equal measure. I was asked to give a lecture at the Orenburg State University (about photography and blogging to promote wildlife conservation) and after reading a first draft to my wife she said, “You can’t keep that Putin joke in there! What if they arrest you or something? It’s … Russia!” I agreed to take it out, but somehow I knew I wouldn’t be able to resist. Was I going to wind up in a Russian prison? What was going to happen to me in this enormous and unknown land? Because, after all, it was, you know…

Russia.

(Insert dramatic background music here.)

******

First Steppes

I step off the plane in Moscow and have a brief adrenalin rush as reality sets in. I can’t understand any of the signs. I can’t even make out the letters. There are just enough characters from the English alphabet that I attempt to sound out the words in my head. But it’s impossible because the rest of the letters are total gibberish. I couldn’t even look them up in my translator app if I tried. Stay calm. The most critical signs are also printed in English.

The Russian language sounds much smoother than I imagined it would, after years of hearing bad impersonations in American films. It is soft and flowing, not harsh and guttural. I find it quite soothing to my simmering anxiety, listening to the people chatting around me.

I seem to fit in well here. Various men begin conversations with me as if I were a local. I think it’s because I have the same shortish, homemade-looking haircut that most Russian men do. (Yes, my wife cuts my hair.) I can only reply to them, “I’m sorry, I only speak English.” And without exception, they smile magnanimously and apologetically with kind looks in their eyes. Though I clearly have an American accent, there is not a trace of animosity, only friendly faces.

If it weren’t for the constant loudspeaker announcements in Russian, I could be sitting in any American airport. These people look exactly like my people.

The security checkpoint, however, is a slightly different experience. The friendly young woman at passport control doesn’t ask me a single question. When I walk through the metal detector there aren’t any employees watching. As I exit, I glance around incredulously for a moment and grab my bag off the conveyor belt. The American border retains its title as the most annoying border crossing in the world.

After a short domestic flight I arrive at my destination: Orenburg. I chose this place because there is a critically endangered animal living nearby that can’t be seen anywhere else in Russia. But we’ll get to that later. The city of Orenburg is known as the Steppe Capital of Russia.

Steppes are grasslands, similar to the Prairies of North America. The view flying in at night is of a vast empty black plain with tiny pockets of lights, like flotillas of lonely boats at sail on a dark sea.

I’m greeted by my translator Anastasia Lukinskaya. Thankfully her English is excellent and I feel incredibly relieved she’ll be accompanying me each day. She and a friend transport me to the Golden Elephant Hotel in downtown Orenburg. Nastya, as her friends call her, chats with me in the back seat as we drive into town. She is cheerful and enthusiastic and I like her immediately. My hotel room is luxurious. Much nicer than any hotel I would ever stay in at home, but the cost is only $50 US. Maybe I could get used to this. Before departing, Nastya hands me a paper bag. “We thought you might be hungry,” she says with a smile as she turns to go.

I sit on my large leather couch and look at the bag. I can’t read the words but the logo is very familiar. Inside is a hamburger wrapped in paper. I haven’t eaten one of these in at least fifteen years back home. I had to come to Russia to get a Burger King Whopper.

******

Bears, Borsht, and Banya: Shaytan-Tau Reserve

A rare fog envelops the steppe as we barrel down rutted gravel roads.

“We have a saying here. There are only two things to worry about in Russia: fools and roads. We have the worst roads in the world,” Nastya says with a look that is half apology and half pride. I tell her that I’ve seen worse and she actually seems a bit disappointed.

We are once again in the back seat, but our companions have changed and our vehicle is now a large pickup truck with a snorkel.

At the wheel is a hardy and handsome Russian man about fifty years of age. He wears an official-looking brown ranger uniform and has short spiky hair. I can’t help imagining that he is the Russian boxer from Rocky IV (Ivan Drago) all grown up and taken a respectable job with the park system. In fact, his name is Vyacheslav Soloviev (“but you can call him Slava”) and he’s the head ranger at Shaytan-Tau, where we are now headed.

In the passenger seat is a young woman named Anna Harabuga, the eco-education and tourism specialist. She has a kind face and smiling eyes and is very indulgent of all my silly questions. We stop at a small village called Kuvandyk to buy some groceries and check out the view from a World War II monument. As Nastya is explaining it to me, I catch my first glimpse of Russian pride over the defeat of Hitler.

After two hours of flat steppe, the terrain begins to buckle and heave. The southern tip of the mighty Ural Mountains rises before us, as though we were looking up the backbone of 1,500 mile-long dragon whose head is cooling in the Arctic Ocean to the north.

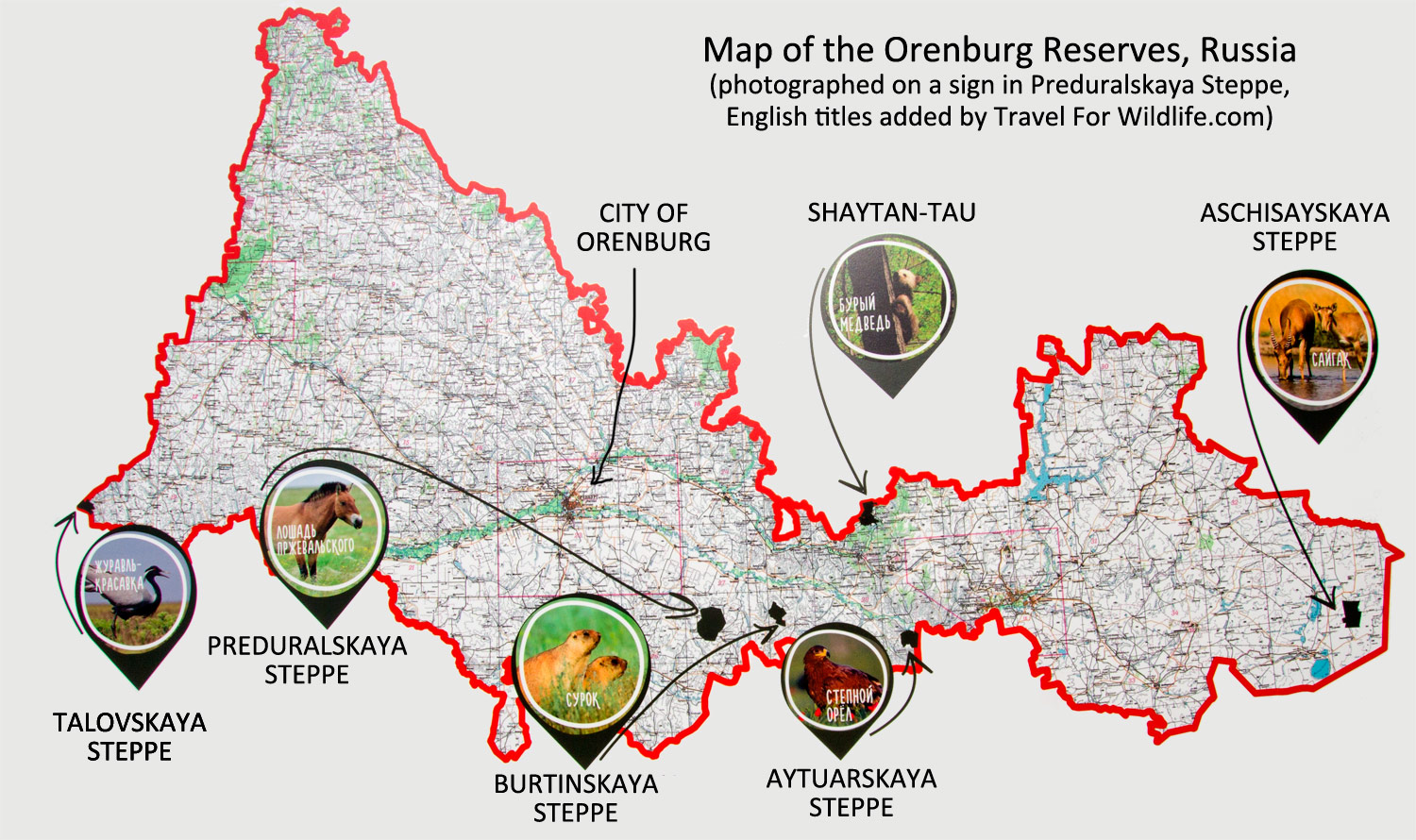

Orenburg is not just a city, but also the name of the surrounding state (more correctly termed an oblast), much like New York, New York. In fact, this state is very similar in size to New York State, stretching 470 miles from end to end. The Orenburg Reserve system is a collection of six separate units sprinkled across the state lengthwise. It is known as Orenburgsky Zapovednik in Russian.

Shaytan-Tau (??????-???) is the newest addition, hardly a year old, and holds the distinction of being the only mountainous and forested reserve on the list.

Because of its unusual terrain, it also boasts an impressive diversity of wildlife, combining the creatures of the steppe with those of the northerly forests. I feel the hairs on my arm stand up as Slava lists off some of the species he’s encountered in the reserve: moose, wild boar, brown bear, wolves, lynx. Holy crap! I had no idea I could be crossing paths with such a charismatic cast of characters.

Blue skies emerge as we crawl up the valley. Nearing the reserve we encounter a beautiful crystal clear river. Although there is a flimsy bridge, Slava chooses to drive right through the river. (What the heck, we have a snorkel.) It’s so much fun that he happily agrees to do it again so that I can photograph him from the bridge.

We arrive at our guesthouse, a barn-shaped building looking across a meadow toward a stony peak. I was informed a bit too late that I should pack slippers for use in the guesthouses, so instead I ‘borrowed’ a pair of slippers from my hotel room this morning. At the threshold, I open the plastic package, place the thin white terrycloth slippers over my toes, and explore. The house is basic but cozy; a kitchen with wood stove, a bathroom, and three guest rooms. Mine has two single beds and a portable heater which is already cranking. It’s early October but already quite chilly.

Slava will be staying in his own house nearby. He spends about a week here at a time while whipping the new reserve into shape, then a few days back home with his family in Orenburg.

I am irresistibly drawn to an ancient set of swings out front, beautifully designed as small boats. This property used to be a summer resort back in the soviet era and these children’s rides are a relict of the period.

The newly created dirt road up into the mountains is slick with mud from recent rains so we can’t head upward, but instead tour around the lower elevations. Magpies and crows patrol the fields and a Common Kestrel devours its kill on top of a power pole.

We stop at the river and breathe in the fresh air.

At each stop, Slava pulls out his knife with a determined look on his face. He is hunting. When he finds his quarry, he deftly reaches down and slices off its head. Mushrooms. As we are not in the reserve proper he is welcome to harvest the meaty fungus wherever it bursts from the grass. Everyone joins the hunt with gusto while I scan for creatures.

Slava tells me he has had two sightings of the elusive Eurasian Lynx in the last two months! On the return trip they drop me off at the edge of the woods so I can walk myself back and enjoy the wilderness.

The birch forest is bursting with color. I feel a special connection to these trees because my mother’s maiden name is Bereza: the Russian word for birch (her father came from the Ukraine). Yet according to an extensive allergy test I received 20 years ago, birch pollen is also the one thing I am most allergic to in the world. I don’t hold it against them and enjoy a quiet walk among the whispering leaves. I watch wide-eyed through the woods imagining a lynx in every shadow, but these animals won’t be seen if they don’t wish to be.

Back at the house, Slava and Anna are preparing dinner. When asked earlier if I’d ever had any Russian food I said, “well I have had borscht.” Slava made up his mind then and there that he was going to prepare some proper Russian borscht for me tonight. Now he is happily puttering around the kitchen, testing this and salting that, chopping here and stirring there, all the while muttering to himself, “takh, takh, takh”. He confides that he would be happy to give up his job as a ranger to become a professional chef.

The meal is delicious and the mood is merry. Slava sings traditional Russian songs in his booming bass voice and Nastya contributes some quiet soothing traditional lullabies. She tells me of an old Russian tradition of welcoming foreign visitors by presenting them a piece of bread with a pinch of salt on top. She grabs a hunk of bread from the loaf on the table, drops some salt on top, and presents it to me ceremoniously. I have officially been welcomed to Russia.

We walk in the dark to Slava’s house and he sings robustly into the echoing woods. He prepares a campfire for us and says “sit down please,” in English. Nastya laughs out loud and tells me it is the one phrase that every Russian knows, the only thing they remember from English class in school. Otherwise, I am totally lost without Nastya’s translations. We sip tea and swap stories and stare quietly into the fire. I imagine a big brown bear with a sleepy look on his face, calmly watching us from the woods just beyond the firelight.

The next morning a cold rain is soaking the hills. We had planned to take an early morning excursion but the roads into the mountain are still a soupy mess so Slava tells us we can go back to bed. My body thinks it is nine hours earlier and I can’t go back to sleep, so I wander out into the pre-dawn drizzle to see what other creature might be silly enough to do the same. Visions of wild boar dance in my head, but after an hour of walking in the silent mist my only reward is a twittering mixed flock of tiny chickadees and long-tailed tits.

After a shower and breakfast, Slava arrives with a 4-wheel-drive vehicle. “Russian jeep” he says. He’s determined to get us up the mountain. We jolt and slide our way up the steep muddy tracks as Slava chats away. I’m in the front seat now so I glance back with a questioning look at Nastya and Anna sitting quietly in the back. “He’s talking about his truck,” she says with a small shrug.

He shows me the new ranger house that is being built in the reserve: a lovely little log cabin. Next to it, the foundation is being poured for the new banya. Banya is a Russian word for sauna, and no self-respecting ranger house would be caught dead without one. Russians take their banya seriously, and I am told I will have my first banya experience this evening. He then lets me take a cruise on his personal ATV (wheeeeeee!) and we continue our rounds. Slava is collecting memory cards from his camera traps.

He is the first ranger in the Orenburg Reserves to conduct a camera trap study and this one has only been running for a few months. In front of each camera is a log with a small trough fashioned in the top to hold a salt block. The target species is moose, and there are plenty of tracks in the fresh mud, proving that the biggest deer in the world was standing right here just this morning.

One of the posts with a camera strapped to it has been knocked to a low angle where moose have raked it with their massive antlers. But it’s not the right time of day to see a moose so we move on to the final trap that was set up to capture photos of wolves. We don’t find any wolf tracks, but next to a puddle in the nearby road we discover the imprint of a large bear paw. Slava tells me he believes it is the track of their biggest local brown bear, a roughly 600 pound male.

We scare up noisy wood grouse as we drive across the grassy meadows, but no larger beasts choose to make an appearance. Slava is apologetic for the lack of sightings but I tell them that I am happy just knowing these creatures are out here and that seeing their tracks is a huge treat for me. It lends an electricity to the air that can’t be felt in the rest of the world where predators have been extinguished.

Back at the guesthouse I take a much needed nap and when I awake it is time for the evening’s festivities. We gather the food and drive to the small banya house next to the river. Slava splits firewood and starts the fire in the stove. Hunks of pork are placed on long metal skewers and grilled over the coals. This is the famous Russian “shashlik” (pronounced like SHASH-loohk). While Slava cooks, the ladies take the first shift in the sauna. It is a humble wooden-planked room with stadium benches inside and it is really, really hot in there. As the sun sets, Nastya takes the traditional plunge into the nearby river.

Then Slava strips down to his bikini underwear and enters the sauna. It is pitch black inside and I can hear him singing loud Russian songs from within. I turn to Nastya with raised eyebrows and a slightly panicked look on my face. I meekly enter the changing room and strip down to my boxer briefs under the light of my headlamp. When I enter the sauna, Slava has stopped singing. The heat stings my nostrils as we sit together silently in the pressing darkness. Occasionally he pours some hissing water onto the stove. He doesn’t speak a word of English, nor I a word of Russian. I half wish he would continue his booming song just to complete the absurdity of the moment. Yet somehow it is still pleasant and relaxing.

Strangely, it is not my first awkward sauna moment. The previous one occurred in the remote village of Togiak, Alaska where I crouched naked in a dark backyard sauna with an incredibly wrinkly ninety-year-old eskimo man who also couldn’t speak a word of English.

With a thump on my knee, he signals it is time to jump in the river. He runs down the steep steps shouting and I climb down gingerly after him. We throw ourselves into the abyss. The frigid water shocks my system and I come up gasping and cursing and wonderfully relieved.

We eat shashlik by the light of Anna’s mobile phone, and drink small shots of strong vodka. (OK, some stereotypes are true.) It is, all in all, an extremely pleasant evening.

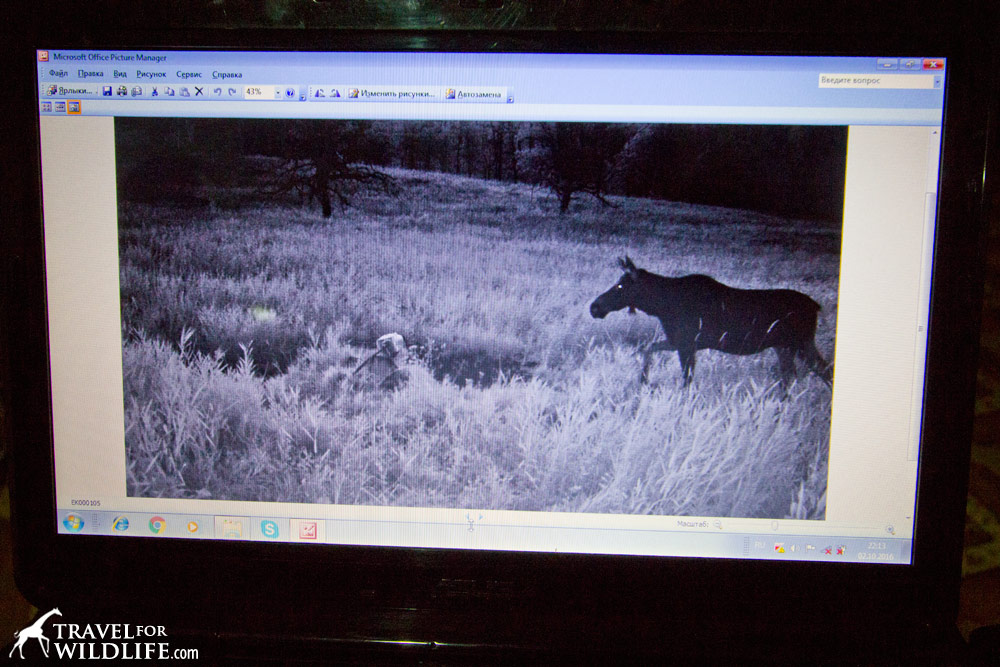

Back at the house we gather around Slava’s laptop with eager anticipation. Looking through camera trap photos is like a treasure hunt, never knowing what surprises might appear.

We are not disappointed. Dozens of moose flash across the screen, from large bulls to mothers with small twins.

There is even a brief appearance by a Roe Deer and a little fox. The big prize is a single brown bear, heading down a track.

We all try to guess which moose is going to knock the pole camera over. “Oh, check out the look on that one’s face. He’s the one”. The moose gets closer and closer in each frame. “Oh! Oh! This is it …” The camera cuts to the next morning, still in position. “ARRHHHH!” we all shout with disappointment. This cycle repeats three times until finally an exceptionally large bull stares into the camera with glowing demon eyes. “Uh oh.” The next frame is a blur, then cuts to black.

******

The Cute Little Blind Guy: Burtinskaya Steppe

Again we are driving through thick morning fog as we leave the mountains behind. Today is Nastya’s 32nd birthday, but as I have no gift to give her, I instead draw a birthday cake on a scrap of paper from my notebook. She is moved by the gesture and tells me she hasn’t had a birthday cake in years.

The steppe begins to flatten as we approach our next destination, the Burtinskaya Steppe division of the Orenburg Reserve. The name means “Place of Wolves” in the Kazakhi language and I am anxious to try to lay eyes on these secretive animals. But as it turns out, we will not be able to spend the night due to an unexpected obstacle. Vladimir Putin is in town. Yes the Vladimir Putin, president of the Russian Federation. He’s here, right now, less than 20 miles away from us at the Preduralskaya Steppe Reserve (where we’re heading tomorrow). There are police road blocks stationed at every intersection along these deserted country roads.

He’s in town to ceremoniously release the aforementioned critically endangered species that can be seen nowhere else in Russia: the Przewalski’s Horse. Six of them have spent the past year in an acclimation corral, and today they will be released into the wild.

It was a last minute thing. Officially, nobody is supposed to know he’s here, yet everybody knows he’s here. So instead of spending the night in Burtinskaya, I’ll be taken back to a hotel in the city of Orenburg.

This leaves us with one afternoon to spend in Burtinskaya Steppe and we intend to make the most of it. I’m introduced to an amiable older fellow with a compassionate face. His name is Victor Shpanagel and he is the head ranger here. The other three rangers join us for tea in the picnic shelter. Via Nastya, I ask Victor questions about the wolves.

They’ve seen three different packs on the reserve. The smallest is just a pair; the largest has upwards of 9 members. The rangers appear to have mixed feelings about the wolves. One time they heard wolves nearby and spotted a female moose rearing up on her hind legs in fright. She bolted straight toward the rangers with a crazy look in her eyes. Terrified, the rangers ran for the trees and scrambled up them. “But I couldn’t make it up,” Victor laughs, “because I’m too old! So I hid behind the tree and ducked from side to side until the moose got tired and ran off.” When the rangers returned to the site, they discovered a placenta and a trail of blood. The wolves had taken her newborn calf. “I know it is nature and we can’t interfere, but it was hard not to feel sympathy for that mother moose.”

Victor takes us for a walk around the eco-trail which has educational signs posted along the way to explain the sights. The landscape here is a transition between the forested mountains of Shaytan-Tau and the bare grasslands of Preduralskaya. Here, rolling hills are covered with short grass but the river valleys and springs erupt with thin patches of colorful trees.

Likewise, the tourism infrastructure here is halfway between the brand new, undeveloped Shaytan-Tau and the well-funded Preduralskaya Steppe.

Another unexpected visitor has arrived in the area. In the last decade, the Eurasian beaver has reintroduced itself into the local waterways. Burtinskaya boasts the largest natural spring in Orenburg, but since the beavers began damming it, they no longer drink from it. Again I get the sense they feel a bit conflicted about this animal’s presence. I am used to hearing this sort of ambivalence about beavers. The beaver is Canada’s proud national animal yet practically every Canadian I meet seems to hate them. Their ability to directly shape and alter the environment is unparalleled in the animal kingdom, except of course by humans, which apparently don’t appreciate the competition.

Although the marmots and ground squirrels have already gone to sleep for the winter, there are still active mounds of dark soil all across the steppe. Yet none of them seem to have an entry hole. On the eco-trail I spy a mound with soil flying into the air so I creep closer to see who is doing the digging. The strangest little round gray head pops in and out at lightning fast speed. His tiny beady eyes are nearly invisible against his velvety gray fur. But two sets of absurdly large incisors jut out of his face at bizarre angles and there appears to be no mouth in between. He looks kind of like a mole but is nearly the size of a ground squirrel. I’m told that he’s called a Slepushonka, which roughly translates as “cute little blind guy”.

The English name, I learn later, is the Northern Mole Vole. They spend their lives underground, digging complex burrows and dining on roots. And they seal the entrance to their burrows with dirt. I am very lucky to catch one expelling soil from his subterranean home. Slepushonka is officially my new favorite animal in Russia.

After a stroll around the eco-trail, Victor takes us for a drive in the reserve. I spot a strange ball in the dirt road and Victor hits the brakes. The shape unfurls into a little snake with a dark zig-zag pattern running down its back. It is a Steppe Viper and she coils into a defensive position as we watch, tasting our scent with her tongue and watching us through beautiful metallic eyes. Although the Steppe Viper is venomous, her primary prey here on the steppe is crickets. We let her get on with her business of warming in the sun and continue our drive.

Small birds leap up from the road and the occasional grouse erupts in a feathery fluster from the dry brown grasses. Assorted hawks, falcons and harriers circle above, scouring the land below. We pass a huge empty nest, a messy pile of large sticks half way up a tree. It once belonged to a Steppe Eagle.

Turning a corner we spook three Siberian Roe Deer next to the track. They explode in opposite directions, two to the left and one to the right. It is so open out here that the only way to hide is to run like hell and disappear over the horizon, which they manage to do within a few short seconds. Ten minutes later I spot them again through my binoculars. The three have happily reunited on a far away ridge.

Parked on grassy peak, we scan a small patch of forest below. Victor tells me that he sees wolves here frequently. Tiny shafts of sunlight break through the blanket of clouds, illuminating brilliant yellow and orange autumn leaves. But no wolves wish to be seen this afternoon.

Back at the ranger house, we slurp our soup in the picnic shelter while wagtails bob and weave on the shed roof beside us. I spend a few more moments watching a slepushonka expelling dirt from her burrow and smile to myself.

I find myself in another lovely hotel room tonight back in the city of Orenburg. Anna won’t be joining us at Preduralskaya tomorrow and as I hug her goodbye I feel a tinge of sadness. Everybody has been so kind and welcoming to me that I’ve grown attached to them very quickly. Before departing she hands me a goody bag of souvenirs from the reserves. The notebook, mug, and tee shirt all bear photos of the legendary creature I’ll be visiting tomorrow, the Przewalski’s wild horse.

******

Preduralskaya Steppe

We arrive at Preduralskaya Steppe (which in English means Pre-Ural Steppe) in the late morning.

To hear about my amazing experience at Preduralskaya you’ll have to read my article Return of the Wild Przewalski’s Horse to the Russian Steppe. Visiting this small herd of Przewalski’s Horses was, without a doubt, the highlight of my visit to the Orenburg Reserves in Russia.

******

The Lecture

We drive back to Orenburg City and I check into my old home at the Golden Elephant. After washing all my socks in the sink like a real babushka, I take a long, long nap.

Nastya takes me to dinner at Russian Revolution, a dark moody restaurant with booming dance music. The only other patrons are a group of five very drunk women dancing lewdly by themselves in the middle of the floor. It is quite entertaining but Nastya is embarrassed and apologetic for them.

That evening we meet some of Nastya’s friends to have a birthday celebration at a local restaurant. The two men who join us, Oleg and Sasha, seem warm and genuine. As we fill our shot glasses with cognac, they make toasts to Nastya and their eyes become watery with emotional tears. I can see why these two are some of her dearest friends. I feel deeply honored to be a part of this intimate moment between a group of such kind-hearted people.

After dinner we all walk down the dark deserted city sidewalks, chatting happily and Nastya occasionally translating for me what they are joking about in Russian. It is a beautiful crisp night and I have a wonderful tranquil feeling walking with these kind people, listening to their soft voices and laughter as the cool breeze washes over us.

I will never forget that moment of perfect acceptance and contentment. It summed up my visit to Russia perfectly. These were not frightening aliens that were out to get me. They were people, just like me. Sweet, compassionate, happy people. I realized that Russia was a mirror image of our own nation. Regular people trying to go about their lives, subjected to the same propaganda that I was in reverse. No matter how our governments may choose to interact, we are all the same.

The next morning we walk to the Orenburg State University. Oleg takes me up to the roof of “the library” which happens to be the tallest building in Orenburg. He leads me around to various meetings with department heads and University directors. It is all very formal and uncomfortable and I do my best to try to appear professional and dignified. I can’t remember the last time I actually had to tuck my shirt into my pants. A student photographer is capturing every official handshake. The icing on the cake is that after the meetings, I go to the bathroom and discover that my fly has been down the whole time. Yep, pretty dignified.

I did give my lecture. And I did make my Putin reference and everyone laughed. No armed guards sprung out of the closet. The students were enthusiastic and we took smiley selfies together afterwards. The dean actually said that he would be happy to have me back again for another lecture one day. I responded to him, with all sincerity, that I would very much like to come back to Russia again.

******

The Future of Ecotourism in Russia

Of course I wasn’t actually the first eco-tourist in Russia, but it certainly felt like it. In reality, nearly 200,000 American tourists visit Russia every year. But the wave of ecotourism development is something new, and I look forward to seeing what other projects develop across this vast nation. I believe Russia has the potential to become one of the great wildlife watching destinations of the world. I think I’d like to see an Amur Tiger next, please.

The Orenburg Reserves are still in the process of preparing for tourists, but soon people from around the world will be able to experience these amazing wilderness regions for themselves. For more information on ecotourism in Russia, you can check out the Dersu Uzala website (view in google chrome and turn on translation) or the Dersu Uzala Ecotourism Project website. For more information on ecotourism in Russia, you can send an email to ecotrails.russia@gmail.com. If you’d like to learn more about the Orenburg State Reserves, visit the Orenburg Reserve website. (Again, you’ll have to turn on translation in google chrome.)

I’d like to give a special thanks to the Dersu Uzala Ecotourism Fund for making my trip to Russia possible, and especially to Nastya Lukinskaya for being a great guide, and Elena Bazhenova for all her hard work organizing my visit.

Disclaimer: This article was funded by a grant from the United States Department of State. The opinions, findings and conclusions stated herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Department of State

If you enjoyed this post, Pin it!

Hal Brindley

Brindley is an American conservation biologist, wildlife photographer, filmmaker, writer, and illustrator living in Asheville, NC. He studied black-footed cats in Namibia for his master’s research, has traveled to all seven continents, and loves native plant gardening. See more of his work at Travel for Wildlife, Truly Wild, Our Wild Yard, & Naturalist Studio.

John Wilson

Monday 2nd of January 2017

Must have been a great trip! I envy your adventure - one of my bucket list countries! Thanks for sharing your adventure Travel safely and play nice! Cheers

Alexander

Thursday 17th of November 2016

hey Hal,

I read your story several times as it is funny to see some many well-known name of places from childhood ( I grew up in Orenburg). When I was a 14 years old, was member of local touristic club ( kind of boy scout clubs in the US) , so we visited these places many times (at that moment it was not reserve) . I shared your article with my friends who live now in different countries and far enough from the city, they are enjoyed and showed the article to their family members and friends who never been to Russia and Orenburg but all them are wanted to read such interesting story in English as most of them are not Russia speakers, so kind it is kind of introduction to their possible future travelling to the home land of their relatives :)

thanks a lot!

Amanda

Sunday 13th of November 2016

Such a great post! I just went to Russia for the first time in October, and while I was mostly in larger cities, I was definitely surprised that many of my conceptions about the country were definitely misconceptions. And while I heard plenty of people talking about how much they like Putin, I also heard plenty of Putin jokes on my trip. ;)

Heather Cole

Saturday 5th of November 2016

What a refreshingly enjoyable piece of writing, the first blog post I've read in it's entirety for quite some time. I had no idea that Russia was such a wildlife haven, certainly sounds every bit as good as an African safari, and the excitement is as much in the anticipation, and, as you say, knowing the animals are out there, than the actual sightings. What a wonderful experience.

Hal Brindley

Saturday 5th of November 2016

Thanks so much for the kind words Heather! I'm so glad you enjoyed it. And congratulations on getting through the whole article. Ha! It did come out ridiculously long I'm afraid! I hope you guys are enjoying your travels!

Simon Pierce

Wednesday 2nd of November 2016

Love this. Great writing Hal!

Hal Brindley

Thursday 3rd of November 2016

Thanks Simon!